The team “spatial regulation of genomes” explores the principles that govern the 3D organization of genomes and its causal relationships with DNA processes such as repair or segregation. Convergent evidences, including from our work, point at major roles for transcription (and associated chromatin state) and structural maintenance of chromosome (SMCs) complexes in shaping chromosome folding in all domain of life, though their precise interplay, as well as role(s) for physical phenomena such as liquid-liquid phase separation, remain elusive. We address our questions mostly in prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular microorganisms, using a combination of synthetic genomics, computational biology, reverse-genetics and genetics approaches. We also enjoy well-established collaborations with physicists (Mozziconacci, Nollmann lab) and teams with skills and interests complementary to ours.

Part of the projects aim at describing and characterizing the regulation and function of the structural changes undergone by yeast and bacterial genomes during the cell cycle, when facing DNA damage or when confronted to environmental changes or viral infection (e.g. Piazza, Bordelet et al., Nature Cell Bio., 2021; Conin et al., NAR, 2022; Cockram et al., Mol. Cell, 2020; Garcia-Luis et al., Nature SMB 2019; Lioy, Cournac et al., Cell, 2018; Lazar-Stefanita et al., EMBO J., 2017; Marbouty et al., Mol. Cell, 2015). For instance, we explore the role of the SMC cohesin, a ring-like structure with ATPase activity originally characterized for its role in sister-chromatid cohesion (SCC) but know recognized as a major player for chromosome folding in cis. Cohesin most likely dynamically organizes chromatin through Loop Extrusion (LE), a process by which it progressively enlarges DNA loops. We are dissecting in collaboration with Fréderic Beckouët (CBI, Toulouse) the molecular regulation of the cohesin complex by partners (Dauban et al., Mol. Cell, 2020; Bastié et al., Nature SMB, 2022), showing that in yeast cohesins involved in SSC represent roadbloacks to loop extruding cohesins in cis, thereby establishing structural constraints on chromosomal domains (Bastié et al., Mol. Cell, 2024), or showing how actively transcribed genes represent permissive roadblocks to incoming extruding cohesins, a phenomena likely common to all species with loop extruding SMC in their genomes (including prokaryotes, and archaea)(Chapard et al., Cell Genomics, 2025).

We also take advantage of synthetic genomics approaches, stemmed from our collaboration with the Sc2.0 project coordinated by Jef Boeke (NYU) (Mercy et al., Science, 2017), and artificial chromosome systems. Synthetic DNA sequences designed in silico and assembled in yeast help us to solve experimental bottlenecks: for instance, we used a synthetoc genomics approaches to design 150 kb DNA regions allowing us to address questions related to homologous pairing in yeast during meiotic prophase (Muller et al., Mol. Sys. Bio. 2018). We recently used artificial chromosomes to explore how a foreign DNA sequence in a host cell follows deterministic sequence-based rules when it comes to transcription activity, chromatin formation, and even 3D organization (Meneu et al., Science, 2025).

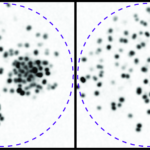

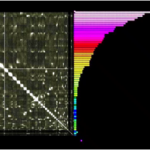

Continuing advances in technology development are an important driver of research progress. We hold a long-standing philosophy to continuously improve or develop new technologies and programs when needed to address our scientific questions. This leads pipelines to analyze genomics data, for instance Chromosight, a user friendly computer vision-based loop caller (Matthey-Doret et al., Nature Commun., 2020), or R-packages such as HiCExperiment in the bioconductor environment (Serizay et al., Nature Commun., 2024; Serizay and Koszul, Bioinformatics, 2024). The programs we develop to analyze and integrate our data are available on the github account of the lab, and below.

Finally, we co-pioneered the exploitation of proximity ligation approaches to solve genomics limitations (reviewed in Flot et al., 2015; Marbouty and Koszul, 2015). For instance, to improve genome annotation thanks to 3D folding (e.g. doing centromeres calling in Hi-C contact maps (Marie-Nelly et al., 2014a). We also developed Hi-C scaffolding (Marie-Nelly, PhD thesis, 2013; Nature Commun 2014b; Baudry et al., Genome Biol. 2020) and Metagenomics Hi-C (MetaHiC), that allows binning and scaffold dozens of genomes de novo from complex microbial communities, while assigning mobile elements to their hosts (Marbouty et al., 2014; 2017; 2020; Baudry et al., 2019). These approaches have opened up new areas of research, which holds potential for both fundamental discoveries and biomedical applications. Performed over time, these approaches allows tracking the propagation of genes or genetic elements of interest throughout a complex ecosystem. We published some of the first programs and pipelines to scaffold incomplete genomes using Hi-C data (instaGRAAL), bin metagenomes using Hi-C (metaTOR), and constantly improved them since. All our proximity ligation programs are open source and freely available on github (https://github.com/koszullab).

Our ongoing research projects include regulation of cohesin-dependant folding of yeast and bacterial chromosomes during the cell cycle ; The influence of transcription on chromosome organization in those species ; and influence of chromatin organization of meiotic double-strand break repair and mitotic genome stability. We are also pursuing the development of contact genomic applications, that we are now applying to a broad variety of questions, including metagenomic analysis, gene flow, etc. Finally, we are trying to understand how eukaryotic and prokaryotic host genomes cope with different kinds of infections, and whether changes in their 3D organization can inform us about some molecular mechanisms at play. The lab therefore welcome all kind of applications by students or postdocs interested to join!

Check out our Github space for code and programs https://github.com/koszullab/