Key words : antimicrobial drug evasion, microbial interactions, microbiome, vertical and horizontal transmission, high and low income countries, epidemiology, biostatistics and dynamic modelling

Antibacterials are back in the pipe and are likely to no longer be lacking with the current develpment of either already known molecules’ class involving either a widening of the bacterial spectrum or structural modifications, either new classes with authentic new mechanisms of action, either new non bactericidal inhibitors of beta-lactamaes, either vaccines against ESKAPE, either new concept of evo–eco drugs which have recently emerged such as microbiota modulators or coumpounds limiting horizontal gene transfert (HGT).

It is however predictable that new resistance mechanisms will emerge and disseminate, sooner or longer after these new drugs being produced and marketed into human use.

The challenges addressed by our research unit are in line with mitigating such as a dissemination and, therefore, the burden of antibacterial resistance ; this in highly contrasting economic contexts: high-income countries and very low-income countries.

Our research unit investigate the 3 following issues :

- How the negative and positive externalities of antibacterials can be accounted in the burden of antibacterial resistance and therefore in the development of antibacterials’ innovations ?

- How to distinguish between (and weigh up) what is linked to the inter-bacterial transmission of resistance genes within human and environmental microbiota, and what is linked to the human acquisition/transmission of resistant bacteria (horizontal or vertical) ?

- How to characterize the intrinsic epidemicity of limit resistant bacteria, in particular toward and within vulnerable populations (hospitalized patients, newborns, etc)?

Resistance burden and drug innovations

The conventional approaches for measuring the burden in terms of “consequence-of-illness” and “cost-of-illness” are not able to rationally anticipate what the populations interest of antibacterial innovations might be. This is because the transmission nature of bacteria. These approaches can account correctly neither positive nor negative externalities of populations antimicrobial exposure. This is even more obvious for the future “evo-eco” drugs, since the foreseeable impact of these compounds is much more expected at the populations level than at the individual one. Here our ambition is to develop new approaches that would make it possible to anticipate the effectiveness (in particular in vulnerable populations such as neonates, elderlies, hospitalized patients) of antibacterial innovations as early as possible during the preclinical phases of the development of these new drugs.

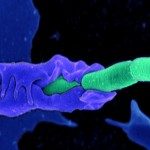

Microbiomes dysbiosis, microbial interactions and resistance dissemination

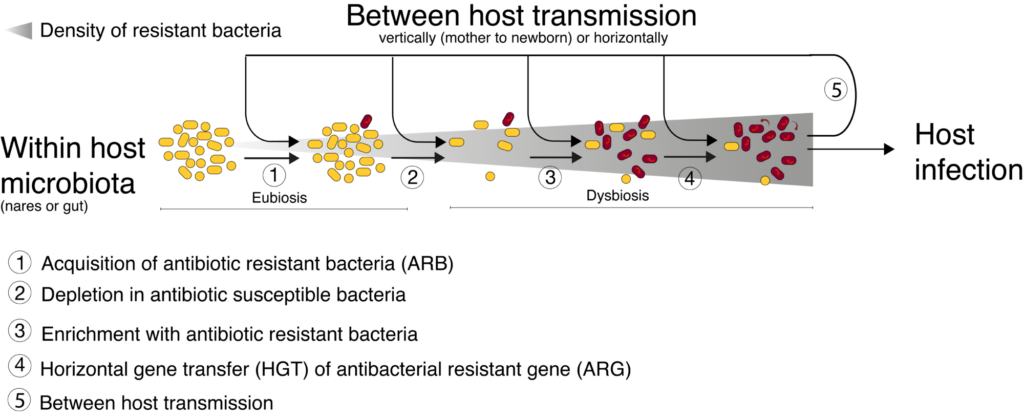

Microbiomes (human and environmental as well) play a pivotal role in antibacterial resistance dissemination. Two potentially synergistic mechanisms are involved in this role (see figure), (i) horizontal gene transfer (HGT) even between different bacterial species, and (ii) microbiome dysbiosis, i.e. quantitative and qualitative modification in its bacterial diversity . In addition, both of these two mechanisms have been suggested to be influenced by drugs residues within microbiome, such as antibiotic residues but also by other drugs( carbamazepine, metformin, proton pump inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti–inflammatory drugs or atypical antipsychotics). Therefore investigating human microbiota become a crucial issue to understand how microbiome dysbiosis and these exposures impact emergence, selection and transmission of ARBs.

Intrinsic epidemicity of resistant bacteria

Within each of the ESKAPE bacterial species[1] in addition to Escherichia coli, there is now enough evidence to make the assumption that not all clonal complexes (CCs) have an identical potential to be transmitted and therefore an identical intrinsic epidemicity. Beside High Virulent Clones (HVC)[2], some of these clones must be considered as High Epidemic Clones”(HEC)[3], based on either sufficiently (i) remarkable global spread or (ii) striking enough remarkable epidemic outbreaks to be published in the international literature[4]. Some of them have been described as expressing some of the most recently identified ARGs, e.g, Enterobacter cloacae CC ST171 and ST78 embedding NDM–7), or as the vehicle responsible for intra–human ARG transmission (e.g, K. pneumoniae ST307 clade VI OXA–181 carbapenemases. Characterizing the intrinsic epidemicity of the various ESKAPE clonal complexs (CC) circulating in healthcare settings is therefore a key issue**. This could be very helpful in anticipating nosocomial dissemination of these CCs and guide the development and use of anti–ESKAPE vaccines.

To investigate these issues we parallel progresse (i) on burden assessments being based either on large-scale medico-administrative databases (high-income countries), or on ad hoc cohorts (low-income countries), and (ii) on the construction of dynamic models to simulate on the scale of micropopulations the clinical and economical benefits of an innovation. We also implement ad hoc epidemiological follow-up both in the community and in clinical units facing high level of drug exposure and ARB infections.

[1] Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp

[2] For example K. pneumonia with capsular serotype K1 or to a lesser degree K2

[3] Often called as High Risk Clones

[4] S. aureus USA300, E. coli (ST131, ST410, ST69, ST393, ST405), K. pneumoniae (ST258, ST307, ST147, ST11, ST101)8, Enterobacter cloacae (ST171 and ST78), Acinetobacter baumannii (ST79), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ST111, ST235 and also ST175, ST233, ST244, ST274, ST277, ST298, ST308, ST357, ST654).