About

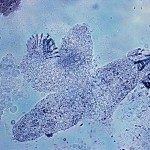

Malaria is a tropical disease due to a parasite named Plasmodium. It is a global health problem,

still causing more than 450.000 deaths each year (mostly African children) and over 200 million

infections (http://www.who.int/malaria/en/). There are four species of Plasmodium that can infect

humans, the deadliest one being P. falciparum. The parasite is transmitted to humans through the bite

of an infected Anopheles mosquito during a blood meal. The parasite will rapidly reach the blood and

stop in the liver where it will invade a cell and multiply inside the cell for approximately one week. This

liver phase is silent and enables the parasite to grow from one parasite to more than 1.000. After one

week, the parasite will make the cell burst and will be released in the blood again where it will invade

red blood cells of the human host. This phase is called the blood stage and is responsible for the

symptoms. Every 48h, each parasite will enter a new cycle in which, from one parasite, it will give

approximately 30 new parasites that will invade new red blood cells. Symptoms are non-specific and

look like a flu: fever, shivering, muscular pain, headache and nausea are the most common ones. If

not treated in time, the disease can rapidly evolve in a life-threatening state, mainly characterized by a

failure of multiple organs and coma. Treatments are available to kill the parasite, but Plasmodium is

becoming more and more resistant to these therapies, especially in South-East Asia where treatment

efficacy is compromised. The threat is that these resistant parasites reach Africa, as it already

happened by the past with the drug chloroquine, because the disease is deadlier there. There is thus

an urgent need to develop new treatments that kills the drug-resistant parasites.

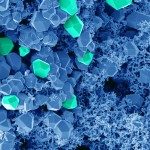

This pathogen uses phenotypic plasticity to adapt to changing environment. Epigenetic

mechanisms play a major role in stage specific development and switch to different life cycle stages

such as transmission stages. Epigenetic mechanisms are tightly regulated in time and are widespread

in humans, animals, plants and pathogens. We are thus aiming to target these mechanisms to kill

Plasmodium parasites and block parasite proliferation and transmission, thus avoiding the generation

of new drug resistance. To this aim we will combine the expertise of chemists and biologists to

develop alternative therapies. Four teams with highly complementary skills will take part to this project:

experts in the chemistry of epigenetic drugs (Arimondo’s team), in the biology and epigenetics of the

malaria parasite (Scherf’s team), in Plasmodium drug resistance in the field (Witkowski’s team) and in

Plasmodium transmission (Baldacci, CEPIA platform). The first two teams have produced very exciting

and promising data based on a recent collaborative study revealing novel chemical structures that

kill very efficiently drug resistant Plasmodium falciparum blood stages. Based on our preliminary

data, the 2-year project aims at (1) identifying new antimalarial drug candidates; (2) validating the

effect in animal models and in the different life cycle stages of Plasmodium and (3)

characterising their mode of action.

We propose here an interdisciplinary approach combining chemistry and biology to find new

drugs to fight malaria. The project should result finally in potent new drugs reaching clinical trials. In

addition, the project will bring a deeper understanding of the epigenetic processes and its actors in

malaria infection. This will open the road to new therapeutic strategies to answer to the urgent need of

therapeutic alternatives in the taming of malaria.