About

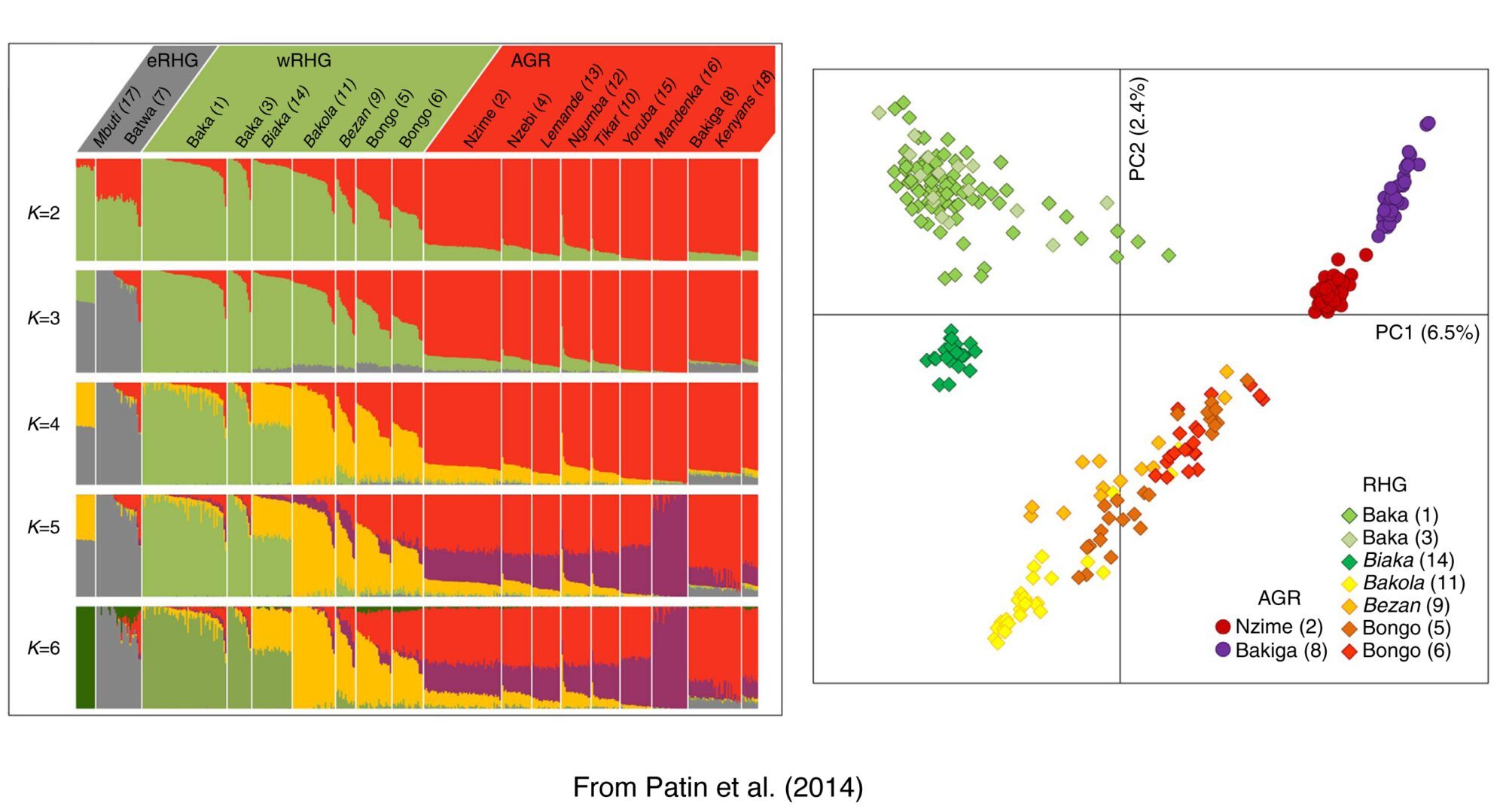

The most important cultural innovation witnessed by modern humans has probably been the transition from a hunter-gatherer nomadic mode of subsistence to an agricultural sedentary lifestyle. This transition occurred in many parts of the world on a massive scale starting 13-10,000 years ago. In addition, farming involved inadequate sanitary practices and zoonosis following the domestication of animals, allowing the establishment of a substantial reservoir of infection and most likely contributing to the rise of infectious diseases. We are interested in understanding how this major transition has affected the demographic and adaptive history of human populations, as well as their epigenomic landscape. To do so, we focus our studies on populations of Bantu-speaking farmers and rainforest hunter-gatherers from central Africa. For example, we have shown that the ancestors of these two population groups diverged ~60,000 years ago, and that the two main groups of rainforest hunter-gatherers separated ~20,000 years ago following a period of major climatic change, the Last Glacial Maximum. We have also shown, based on genome-wide data, that hunter-gatherer and farmer populations have strongly differed in their population sizes over time, and that these differences precede the introduction of agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa.

We are now evaluating how demography and lifestyle have affected the efficiency of purifying selection in these populations, as well as developing methods to investigate the occurrence of adaptation through various evolutionary mechanisms (i.e., classic sweep model, selection on standing variation, polygenic adaptation and adaptive introgression).