Bacteria are present in the most diverse ecological niches of the planet, including in our own body. They are capable of acquiring new features through the acquisition of genes from other bacteria. Particularly important examples include the acquisition of genes conferring resistance to antibiotics, novel virulence traits, or microbial defense tools. The acquisition of these new genes has the potential to disorganize the other genetic elements and hinder the function of the bacterial cell, thus affecting the competitiveness of bacteria. Consequently, bacterial adaptation lies in a conflict between the advantages of acquiring beneficial genes, and the need to maintain the organization of the rest of its genome.

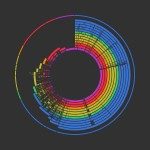

Previous evidence indicated that some species of bacteria accommodate exogenous genetic information in specific hotspots. In order to clarify the function of these reservoirs, researchers from the GEM lab of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, examined more than 900 bacterial genomes, including the agents of some of the deadliest infectious diseases (plague, cholera, meningitides, etc), and noted that these nearly ubiquitous hotspots are not very numerous but include most recently acquired genes. The genes they contain are very diverse and are often lost when lacking beneficial effects. Yet, some of these genes carry clear advantages. For example, they include the majority of antibiotic resistance genes. The genetic content of these hotspots is subject to constant renovation, which allows for its diversification, ultimately facilitating continuous adaptation to different conditions.

This study, recently published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, concludes that bacteria effectively circumscribe the flow of genetic information to a small number of locations in their genome, ensuring a balance between the need to acquire new information and the need to keep the genome organized. These hotspots are treasure troves of the novel functions that are responsible for bacterial evolution.