Présentation

Despite the immense and encouraging progresses made over the last decade, malaria remains a major public health concern. Intensifying efforts against malaria along with an unprecedented increase in public and private funding have allowed reducing the global mortality rate by 45 % compared to 2000 and by 49% in sub-Saharan Africa[1]. The strategies used were mainly based on: i) vector control measures (Long-Lasting Insecticides Impregnated Nets and indoor spraying) and ii) the prompt management of malaria cases at peripheral level (biological diagnosis of suspected malaria cases with malaria rapid diagnostic test and treatment of positive cases with new antimalarial drugs combinations). It is now obvious that the implementation and the global use of ACTs (Artemisinin Combined Therapies), combining a fast-acting artemisinin derivative (ART) and a slower-acting partner drug (i.e. amodiaquine, mefloquine, lumefantrine or piperaquine) has greatly contributed to the malaria endemicity decrease, especially in areas of low transmission such as Cambodia1. As a consequence, the long-term goal has now shifted from control to elimination. At present, numerous reports show that malaria epidemiology is rapidly changing, leading a special and new focus of malaria–targeted interventions and research on Plasmodium infections in low transmission and pre-elimination areas (including Plasmodium falciparum but also other species like P. vivax), its reservoirs (in human and vectors) and the development of innovative tools needed for achieving this laudable goal.

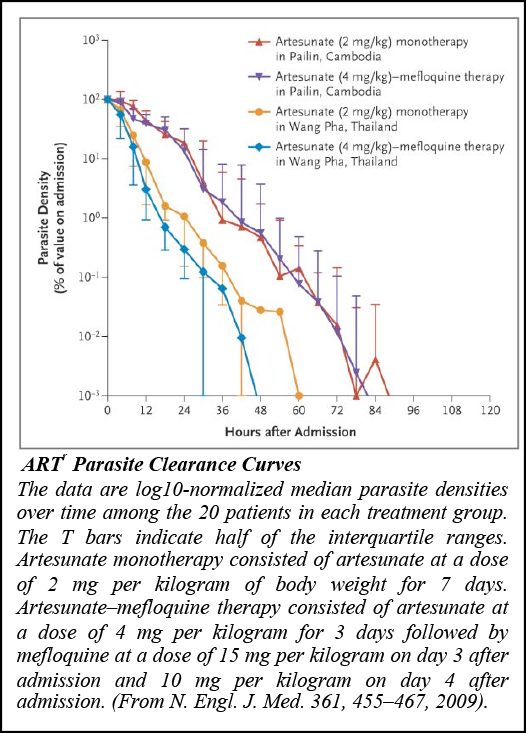

The major issue, which can wipe out the acquired progresses and threaten the ambitious goal of the worldwide malaria elimination is the decrease of the efficacy of antimalarial drugs, a recurrent problem observed with previous generations of antimalarials. Recent data show that the efficacy of the most performant Artemisinin Combined Therapies (ACT) for treating falciparum malaria is declining in Southeast Asia, particularly in western Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar and Vietnam. Initially, it was considered that resistance to ART derivatives was unlikely to be selected, due to the very short half-life of these compounds. Unfortunately, and likewise previous observations made for chloroquine for instance, this was contradicted in 2008 by the emergence of ART-resistant parasites (ARTr), clinically observed for the first time along the Thai-Cambodia border [2]. These first observations were followed later by additional descriptions of hotspots of ARTr in Cambodia[3] and other neighbouring countries in the Great Mekong region: Thai-Myanmar border[4], Myanmar[5] and Vietnam[6]. Currently, the first major challenge is to avoid the spread of these ARTr parasites to Africa, as observed earlier with CQ- and SP-resistance. From 1980 to 2000, annual malaria incidence was indeed estimated to 3 million deaths, occurring mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa. The emergence and the spread of South East Asian P. falciparum CQ- and SP- resistant parasites to Africa was the main cause of this dramatic situation.

The selection of ARTr parasites strengthens the need to continuously fill the pipe of new antimalarial candidates, which represents another main challenge to allow maintaining an efficient pressure on malaria via a refreshed therapeutic arsenal. In this context, the projects of the group will remain a trade-off combining knowledge and translational R&D science, focused on 2 main subjects: decipher the biological role of the Plasmodium subtilisin-like proteases SUB1 & 2 during the parasite egress from and subsequent invasion into host cells and of the K13-kelch protein in ARTr. As proven efficient these last years, a synergic multi-disciplinary approach involving chemo-genetic, structural and biochemical biology, is being pursued in collaboration with D.Ménard (IP Cambodge) and Sanofi R&D to select for SUB1 and/or 2 inhibitors to eventually define new antimalarial candidates.

[1] WHO World Malaria Report (2014)

[2] Noedl et al, N Engl J Med 359, 2619-2620 (2008) & Dondorp et al, N Engl J Med 361, 455-467 (2009)

[3] Amaratunga et al. The Lancet infectious diseases 12, 851-858 (2012).

[4] Phyo et al. Lancet 379, 1960-1966 (2012)

[5] Kyaw et al. PLoS One 8, e57689 (2013).

[6] Hien et al. Malar J. 11, 355 (2012)