Link to Pubmed [PMID] – 25092302

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014 Aug;111(33):12127-32

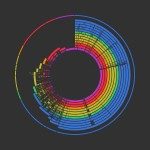

Integrated phages (prophages) are major contributors to the diversity of bacterial gene repertoires. Domestication of their components is thought to have endowed bacteria with molecular systems involved in secretion, defense, warfare, and gene transfer. However, the rates and mechanisms of domestication remain unknown. We used comparative genomics to study the evolution of prophages within the bacterial genome. We identified over 300 vertically inherited prophages within enterobacterial genomes. Some of these elements are very old and might predate the split between Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. The size distribution of prophage elements is bimodal, suggestive of rapid prophage inactivation followed by much slower genetic degradation. Accordingly, we observed a pervasive pattern of systematic counterselection of nonsynonymous mutations in prophage genes. Importantly, such patterns of purifying selection are observed not only on accessory regions but also in core phage genes, such as those encoding structural and lysis components. This suggests that bacterial hosts select for phage-associated functions. Several of these conserved prophages have gene repertoires compatible with described functions of adaptive prophage-derived elements such as bacteriocins, killer particles, gene transfer agents, or satellite prophages. We suggest that bacteria frequently domesticate their prophages. Most such domesticated elements end up deleted from the bacterial genome because they are replaced by analogous functions carried by new prophages. This puts the bacterial genome in a state of continuous flux of acquisition and loss of phage-derived adaptive genes.