About

Summary of the project

- More than 60% of infectious diseases in humans are caused by pathogens likewise circulating in domestic animals and wildlife. Most of these pathogens are viruses whose genome is an RNA molecule. RNA viruses are characterized by their genetic diversity, a population structure in quasispecies, a high level of genetic plasticity by recombination or reassortment, for some the ability to establish persistent infections, and the ability to cross species barriers and to quickly adapt to environmental changes. Among RNA viruses, coronaviruses (CoVs) are unique in that, on the one hand, they seem to have a significant resistance despite their nature as enveloped viruses, and on the other hand, they have the largest known RNA genome. CoVs infect many mammalian and avian species, and a number of cases of successful emergence that have resulted from a crossing of the species barrier, have been documented in veterinary medicine. Special interest in human medicine has been given to CoVs since the outset of the SARS outbreak in 2002-2003, a result of crossing the species barrier starting from a bat reservoir.

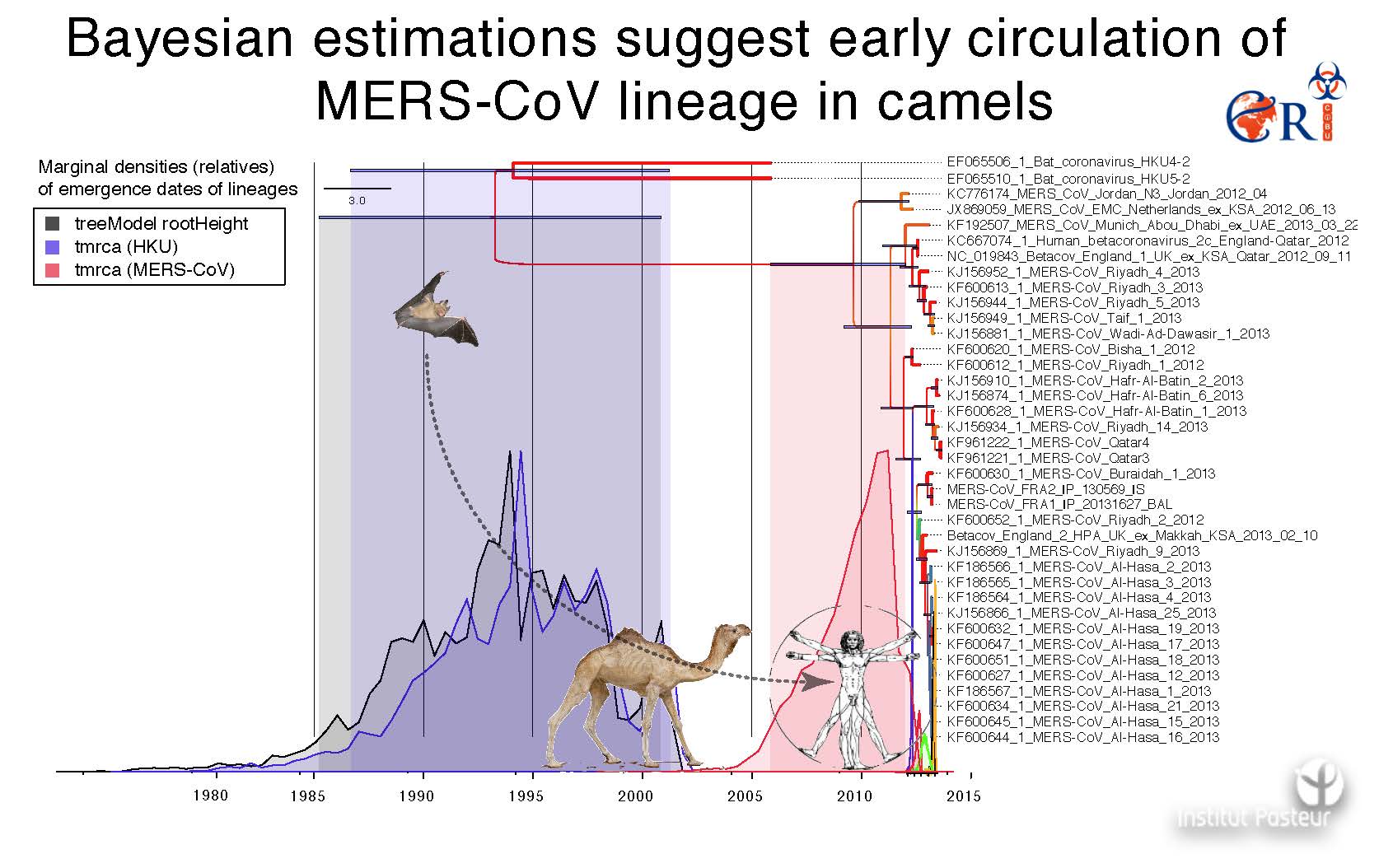

- One of the main features of the EPICOREM project is its implication in current events. Four human CoVs currently circulate in humans and are responsible for respiratory infections of varying severity. Current studies show that HCoVs, along with Rhinoviruses, are the two most prevalent respiratory viruses in the general population, and among the most prevalent in the population of patients hospitalized for a respiratory infection. Very recent identification (September 2012) of HCoV-EMC, a highly pathogenic CoV with a case fatality rate of over 50% among the 9 cases now described subjects CoVs to close monitoring. An HCoV-EMC alert is underway, particularly in the countries of the Arabian Peninsula, which places our study in the midst of current issues.

- The EPICOREM project also adheres to the innovative “One Health” approach, working from a broader, holistic vision of viral ecology within different ecosystems. It proposes a horizontal study of CoV infections reaching from wildlife to humans. This project also encompasses many aspects of coronaviral ecology: evaluation of circulation in different human and animal populations, the study of the diversity of CoV strains circulating in populations where CoV screening is performed, the study of CoVs in animal populations where no data are available, the study of key factors in transmission between hosts, the conditions of adaptation of the virus to various constraints (bottleneck, pre-existing immunity, anti-viral molecules). Improved knowledge of the ecology of viruses will clearly allow for a better understanding of the dynamics of CoV infections in various animal and human populations, and thus the rapid and early detection of emerging variants that are particularly pathogenic.

- The multidisciplinary ambition of this project has brought together researchers involved in a wide range of disciplines: human virology, animal virology, evolutionary biology, phylogenetics, zoology, ecology, epidemiology, and immunology. Such a team of specialists guarantees the feasibility through the acquisition of samples relevant to the interpretation of epidemiological and phylogenetic results. The current urgency as well as the innovative quality of the EPICOREM project will prove attractive to French experts on coronaviruses, and other experts in wildlife, and enable complex cross-referencing and data verification within the consortium established.

Context, position and objectives

-

Objectives, originality and novelty of the project

-

Coronaviruses have a wide spectrum of hosts including a great number of both mammalian and avian species. The pathologies for which they are responsible are essentially respiratory and enteric. Their severity is variable with respect to the host and its immune status. The first animal coronaviruses were described in the 1930s: the IBV or “infectious bronchitis virus” in domestic fowl, the “transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus” in domestic pigs, and the MHV or “mouse hepatitis virus”. These viruses, responsible for serious pathologies in these species, were first studied in veterinary science. Human coronaviruses OC43 and 229E were described in the 1960s, but have attracted limited interest because of the mild respiratory symptomatology which they were linked to.

-

The evolutive and emerging potential of coronaviruses came into the limelight during the 2002-2003 SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) pandemic. The event of the SARS pandemic claims several features that are unique to it: it was the first of the 21st century pandemics; it was the first pandemic to benefit from Internet networking along with tight international collaboration between research laboratories; and the first to be brought under control thanks to the rapid launching of sound health policy.

-

The long-term effects of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) pandemic infection constantly remind us of the permanent risk of emergence of zoonotic pathogens spreading from their animal reservoirs to humans, and the need to be brought under control as quickly as possible. The economic cost of such control is not limited to expenditures in human and animal health; it is widely encumbered by the suspension of social life, including trade. Thus, the economic cost of the SARS pandemic was estimated at between 30 and 50 billions USD, though the virus circulated only 8 months in the human population and infected less than 9,000 individuals on the planet. A deeper understanding of the ecology of zoonotic infections, especially at the interface between humans and other animal species, proves necessary for improving prevention measures to the risk of emergence. Such thinking is an integral part of the new “One Health” approach that incorporates broader, more holistic perspective to the continuum between ecosystems. This approach allows us to bring forth levers of preventive action, namely rapid detection of an “abnormal” phenomenon and the implementation of a rapid and adequate response (figure 1).

-

Following the SARS pandemic, two other coronaviruses that infect humans (NL63 and HKU1) were identified. Along with paramyxoviridae and influenza viruses, the coronaviridae family belongs to the three viral families most closely monitored in the context of emerging diseases. The identification last September of the coronavirus HCoV-EMC, responsible for a SARS-like syndrome and acute renal failure in humans, provides a clear warning that this risk is of current concern. Nine cases, to date, have been reported and confirmed from a virological viewpoint, all from the Arabic peninsula. This new coronavirus is genetically close to some bat coronaviruses, and it evokes the problematic question of whether it is a matter of a sporadic crossing of the species barrier without major consequences in epidemic terms, or if the virus will acquire the ability to effectively be transmitted from human to human, and to constitute a real danger of successful emergence.

- The objective of the present proposal arises from the context of this investigation. We propose a horizontal study of coronaviruses – viruses with a high evolutive potential -, and their impact on different animal populations as potential sources of human infection. The primary aim of this project is a transversal investigation of the circulation, the diversity, and the transmission dynamics of coronaviruses in French territory, between the different ecosystems represented, from wildlife (bats, rodents, wild boar, lagomorphs), domestic carnivores (dogs, cats), livestock (cattle, horses, pigs, rabbits), and the avian reservoir to Human.

- The first goal is to measure the presence and the impact of coronaviruses in the different ecosystems shared by these viruses (seroprevalence, molecular detection, amplification in cell culture).

- The second is to perform a molecular and phylogenetic analysis of isolated cultures taken from different ecosystems.

- The third objective is to study the key factors of transmission and the adaptation of coronaviruses under different evolutive constraints.

- The originality of this project is found in its horizontal approach to the ecology of coronaviruses, from wildlife (as yet unexplored in our territory) to Human. This approach imposes a multidisciplinary character on the researchers involved. In this way, our project brings together epidemiologists, zoologists, molecular biologists, evolutionary biologists and virologists working in the fields of veterinary and human medicine. Most of them hold expertise in the biology of coronaviruses.

-

State of the art

Coronavirus biology : significant features

- Coronaviruses (CoVs) are enveloped viruses that have positive-sense, non-segmented RNA genomes that are 27-32 kb in length. The viral particles are pleomorphic, and their crown aspect – visible under the electron microscope – is due to the presence on the envelope of mace-shaped spikes 20nm high and expressing the high variable S protein. The basic gene organization and replication are well conserved for all CoVs. The genome includes 9 genes: gene 1 represents the first two thirds of the molecule and consists in two very large open reading frames, 20 kb in length (ORFs 1a and 1b), that encode all the 16 replicase/transcriptase proteins (nsp1 to 16). Genes 2-9 represent the remaining 3’ one-third and encode the structural proteins ((HE)-S-E-M-N) as well as a variable number of accessory proteins. The CoV RNA genome is linear and contains untranslated regions (UTRs) at the 5’ and 3’ ends. CoVs belong to the Nidovirales order and thus generate not only new positive RNA genomes, but also a 3’-nested set of sub-genomic mRNAs (sgRNAs). All these RNAs and sgRNAs are 3’-coterminal and contain an approximatively 70 nt 5’ leader sequence. The sgRNA transcription involves an original discontinuous event termed transcription attenuation during negative strand RNA synthesis. During the negative strand synthesis, RdRp is able to dissociate from its template and then re-associate with the leader TRS located at the 5’ end. Among the RNA+ viruses, CoVs clearly distinguish themselves by encoding the most complex and largest genomes. The low replication fidelity of RdRp, due to the possibility of the generation of an enormous number of viral progeny, is thought to be a key determinant of RNA virus quasispecies (defined as mutant clouds or mutant spectrum that can act as a unit of selection) diversity, adaptation, and virulence. Moreover, recombination events shape the viral population structure, promoting cross-species transmission. The high recombination frequency is likely due to the very large size of the genome paired with a replication complex naturally equipped to associate and reassociate from the template RNA. Recombination combined with high mutation rates allow for the rapid evolution of the CoV genome, which undergoes high positive selective pressure during emergence and host-shift events. Recently, some authors discussed and developed viral systems to explore the role of RNA replication fidelity in RNA viral evolution and pathogenesis. RNA viruses have been characterized by constitutively low replication fidelity, and some studies using poliovirus (RNA genome 7 kb) have demonstrated that any increase in RNA replication fidelity result in decreased viral fitness in vitro and pathogenicity in vivo, suggesting the existence of a balance between genome stability (no accumulation of deleterious mutations) and the diversity required for survival. The CoV genome is the largest RNA virus genome, and probably possess mechanisms to limit the excessive numbers of deleterious mutations leading to a dramatic loss of fitness while concomitantly maintaining the genetic diversity required for adaptation to new environmental conditions. In contrast to others positive strand RNA viruses, CoV have expanded replicase fidelity by encoding a 3’-to 5’ exoribonuclease activity ExoN in nsp14. Recent studies suggest that nsp14 ExoN likely serves as mediator or regulator of a more complex RNA proofreading machine, and then the RNA replication fidelity may be adaptable to environments and selective pressures rather than a fixed determinant. In conclusion, within RNA viruses, the lack of more complex genomes exceeded those of the CoVs suggest that these viruses represent the upper limit of replicating RNA molecules, continually negotiating the abundance of the quasispecies and the genome stability.

-

CoVs infect many mammalian and avian species, causing acute and persistent infections. Their main tropism is triple: respiratory, enteric, and neurological. Recently, a new taxonomic nomenclature (2011) divided CoVs into 4 genera, conveniently tagged alpha-, beta- (from beta-a to beta-d), gamma-, and delta-coronaviruses, within the Coronaviridae family, within the order Nidovirales. The number of identified CoVs increases rapidly from the discovery of SARS-CoV in 2003 today, and the classification became increasingly complex (Figure 2).