About

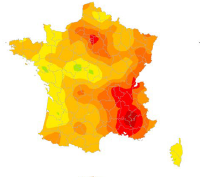

The Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases Unit works closely with public health agencies in France and abroad to provide modelling support during epidemics so that our assessments can contribute to evidence-based decision making and planning. For example, when Zika virus affected Martinique island in 2016, in collaboration with Santé Publique France, we developed mathematical models to characterize epidemic spread and anticipate needs in healthcare facilities (e.g. number of ventilators, number of beds) to manage Zika-related complications. These analyses were shared with Direction Générale de la Santé to inform planning. Similarly, we developed models to assess the risk of dengue epidemic in Reunion Island in 2018-2019 with a view to support local planning. We have other collaborative projects with Santé Publique France on a variety of subjects including the mapping and prediction of influenza epidemics or the study of measles immunity and spread in France. Some of our staff members spend 50% of their time at Santé Publique France to ensure modelers, epidemiologists and Public Health professionals can effectively collaborate and learn from each other.

We also provide similar assistance to our international partners. For example, when Madagascar was affected by a major plague epidemic in 2017, our Unit was heavily involved in the response. Three postdocs of the Unit were embedded to the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar (IPM) where the Plague Reference Center is located for the duration of the epidemic to provide technical, statistical and modelling support. The real-time assessments performed at the time were pursued into longer term research projects on plague that aim in particular to better understand the epidemiology and the transmission dynamics of plague, assess the performance of existing diagnostics and optimize the case classification.

During the large Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2013-2015, we supported our colleagues from Institut Pasteur de Dakar that were heavily involved in the outbreak response in Conakry, the capital city of Guinea. With them, we performed detailed analyses of Ebola chains of transmission in the city so that we could characterize how Ebola was spreading in different settings (e.g. community, hospital/ETC, funerals), assess the effectiveness of interventions targeting each of these settings and determine where additional resources should be allocated.

When Zika emerged in the Americas, we provided one of the first estimates that quantified the association between Zika infection in pregnant women and fetal microcephaly using data collected from a previous outbreak in French Polynesia. The study also highlighted that the risk of microcephaly was highest when infection occurred in the first trimester of pregnancy.